BBC

BBCVictoria Roshina disappeared in August 2023 in the part of Ukraine now occupied by Russian forces.

It took nine months for the Russian authorities to confirm the journalist’s detention. They didn’t give any reason.

This week, her father received a terse letter from the Defense Ministry in Moscow informing him of Victoria’s death, aged 27.

The document said that the journalist’s body would be returned in one of the exchanges organized by Russia and Ukraine for soldiers killed on the battlefield. The date of death was set as September 19.

Again, there was no explanation.

Victoria vigil

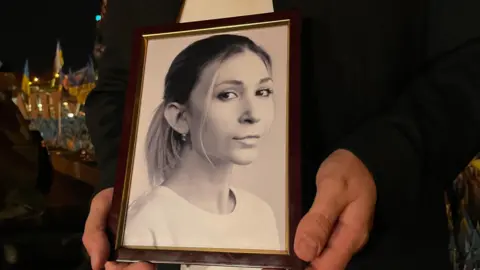

This weekend, friends gathered to commemorate Victoria on the square in central Kyiv. They took up their positions on the steps holding her picture, her young face smiling at the small crowd.

“She had tremendous courage,” one woman began the tribute.

“We will miss her terribly,” said another, as she walked away, her eyes full of tears.

Victoria’s stories were snapshots of life that Ukrainians couldn’t get anywhere else.

Reporting from the occupied territories of Ukraine was extremely dangerous, but her colleagues remember how desperate she was to go there, even after she was arrested and detained the first time, for ten days.

Sergey Dolzhenko/EPA

Sergey Dolzhenko/EPA“Her parents used to call us and tell us to stop posting it, but we never posted it!” recalls one of her former bosses.

“All her editors tried to stop her. But it was impossible.”

Eventually, the young reporter became independent to publish herself, and when she returned, newspapers bought her reports.

Most strikingly, she never used a pseudonym although she wrote publicly about the “occupied” territories and referred to those who collaborated with the Russians as “traitors.”

“She wanted to provide information about how those cities are living under the siege of the Russian army,” Sevgil Musayeva, editor-in-chief of the Ukrainska Pravda newspaper, told the BBC.

“It was absolutely amazing.”

Detention

Victoria’s father previously described how she set off through Poland and Russia last July, heading to occupied Ukraine.

It was a week before she called to say she had been interrogated at the border for several days.

All we know for sure after that is that by May she was in Detention Center No. 2 in Taganrog, southern Russia, a facility so notorious for its brutal treatment of so many Ukrainians that some called it “Russia’s Guantanamo.”

According to the Human Rights Media Initiative, another Ukrainian national released from Taganrog last month told Victoria’s family that she saw the journalist on September 8 or 9.

Then there was reason for hope.

“I was 100% sure that she would return on September 13 this year. My sources gave me 100% guarantees,” says Musaeva, from Ukrainska Pravda.

She was told that Victoria would be included in one of Ukraine and Russia’s regular prisoner-of-war exchanges, scheduled for the middle of last month.

“So what happened to her in prison? Why didn’t she come home?”

Victoria was transferred with another Ukrainian woman, but neither was included in the prisoner exchange.

“This means that it has been transferred to another place,” says Tetyana Katrichenko, director of the media initiative. why there? We don’t know.”

She says it is not a normal practice before the swap.

Lefortovo prison in Moscow is run by the Russian Federal Security Service and is used for those accused of espionage and serious crimes against the state.

They may have taken her there to start some sort of court proceeding or investigation. “It happened to other civilians taken from Kherson and Melitopol,” says Tetyana.

The BBC learned that Victoria’s father spoke to her in prison on August 30.

At one point, she called for a hunger strike, but that day her father urged her to start eating again and she agreed.

“This needs to be investigated. It also means that we will blame her, in part, and not the Russian Federation, as we should.”

The Ukrainian intelligence service confirmed Victoria’s death and the prosecutor’s office changed its criminal case from illegal detention to murder.

In Russia, Victoria has never been charged with a crime, and the circumstances of her detention are not known.

“A civilian journalist… was arrested by Russia. Then Russia sends a message that it’s dead? Ukrainian MP Yaroslav Yurchyshyn told the BBC in Kyiv.

“It’s murder. Just killing hostages. I don’t know another word.”

Russia did not comment.

Civilian hostages

Since the beginning of the large-scale Russian invasion, large numbers of civilians have been transferred from areas of Ukraine that Moscow has overrun and now controls.

Like Victoria’s family, desperate relatives are left with little or no information about their whereabouts or health, and have no idea whether they will return home.

To date, the media initiative has compiled a list of 1,886 names.

“There are all kinds of people, including former soldiers, police officers and local officials like mayors,” says Tetiana.

“And of course there may be a lot we don’t know about.”

Neither lawyers nor the Red Cross can reach him, and even if someone’s location can be confirmed, returning him home is almost impossible: civilians are rarely exchanged.

Natalia Hominiuk/Hromadsky

Natalia Hominiuk/HromadskyVictoria’s friends and colleagues say they will not rest until they investigate what happened.

“Her life was her work,” says Angelina Kariakina, a former editor at Hromadske. “He is a rare type of person who is very determined.”

“I’m absolutely sure that the way she wants us to remember her is not to stand here and cry, but to remember her dignity,” she says.

“And I think what’s important for us as journalists is to find out what she was working on — and to finish her story.”

“Internet practitioner. Social media maven. Certified zombieaholic. Lifelong communicator.”