After four years of continuous campaigning and five election cycles, the election finally ended in a knockout. While coalition negotiations have yet to officially begin and there may theoretically be more surprises in store, it is now likely that Netanyahu will get his wish and be able to put together a right-wing coalition.

Much has been written about the elections and their effects at home and abroad. This column does not seek to add to this discussion.

Instead, as we have done throughout the campaign, we will focus on the data, answering two key questions: What happened to turn an election so close into a relative explosion? And what does this mean to advance the ballot in Israel?

Throughout the four-month campaign, voting has been choppy, with Netanyahu’s blocs and anti-Netanyahu blocs hovering around the 60-seat mark. in our area The final column before the electionwe note that two things can alter this and create a markedly different outcome: the differential participation ratio and the threshold.

This is exactly how it is played. Simply put, the varying turnout ensured a victory for Netanyahu’s bloc, and the threshold ensured a relatively wide margin.

Let’s consider them one by one.

Transformation

This was not an election based on persuasion. With so much water under the bridge, the prospect of making large numbers of voters change positions always seems unlikely. Thus, a large part of the campaign was about generating a mixed turnout, mobilizing the convinced rather than persuading the undecided: bringing more supporters to the polls than the other party could.

The first thing to note is that overall participation has actually gone up, from 67% in 2021 to 71%. Regardless of everything else, it is remarkable that the Israeli public’s response to elections after elections is actually to go to vote in greater numbers.

But more importantly, who went to vote in greater numbers and who did not. Center- and left-leaning cities in the center of the country – such as Tel Aviv, Herzliya, Kfar Saba, Hod Hasharon, and Ra’anana – have seen virtually no change in turnout since 2021. In contrast, right-leaning cities, such as Beersheba, Jerusalem, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Tiberias, and Kiryat Gat, have seen Afula increases turnout by three to seven percentage points.

The far-right Otzma Yehudit party Itamar Ben Gvir gestures to supporters at the campaign headquarters in Jerusalem early November 2, 2022, after voting in the national elections ends. To the left is Rabbi Dov Lior. (Galaa Merhi/AFP)

Thus, the four percentage point increase in turnout came largely from right-leaning regions.

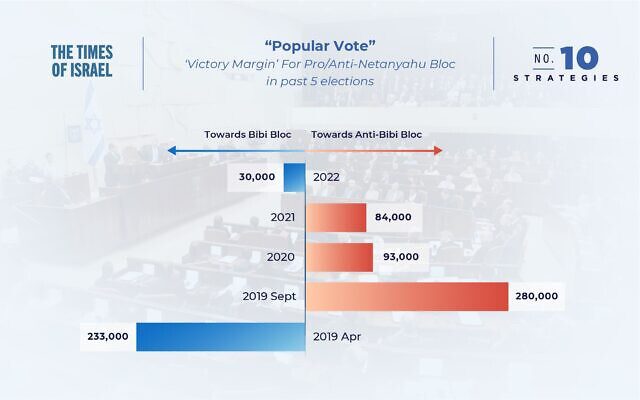

A look at the raw voting numbers makes this point more clear. In 2021, 2.22 million Israelis voted for parties opposed to Netanyahu, compared to 2.13 million for parties loyal to Netanyahu. This time, while the non-Bibi bloc increased its votes by 5 percent, to 2.33 million, Netanyahu’s bloc grew by 11 percent, to 2.36 million. Overall, Netanyahu added 230,000 votes to his bloc from the previous round, while the other party added half that number.

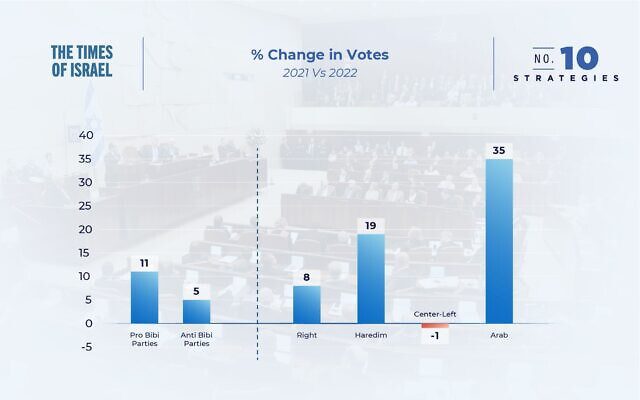

What happened is more evident when we divided the blocks into their components:

On the right, the biggest shift was an unprecedented turnout among supporters of the ultra-Orthodox parties, who managed to increase their voter turnout by 19 percent. Gains among the non-Haredi right (Likud, Religious Zionism and Jewish Home) were more modest, but nonetheless large, 8%.

In contrast, the Zionist center and left (Yesh Atid, National Unity, Labor and Meretz) saw a 1% decrease in their electorate despite the expansion of the electorate, indicating the failure of their attempts to motivate and mobilize their electorate.

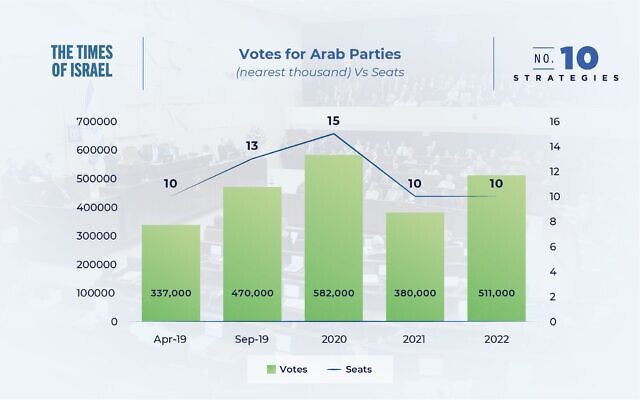

After weeks of talking about the Arab turnout, Arab citizens finally came out in droves, with the vote for Arab parties increasing by 35%. This, however, was ultimately unable to make up for the dip among the center-left.

In total, Netanyahu’s bloc won by a very narrow margin the “popular vote” (a controversial and highly questionable concept in this context, but interesting nonetheless) for the first time since April 2019.

threshold

While Netanyahu’s narrow “victory” of 30,000 votes explains how his bloc would have reached 61 or 62 seats, it doesn’t explain his large majority. So we need to look at the threshold.

As noted throughout the campaign, Netanyahu built his bloc in the best way: four parties, each with a surplus vote-sharing agreement, with one other, smaller party, attacked him mercilessly to ensure he got enough votes. In total, his mass “wasted” about 56,000 votes, or 1.5 seats.

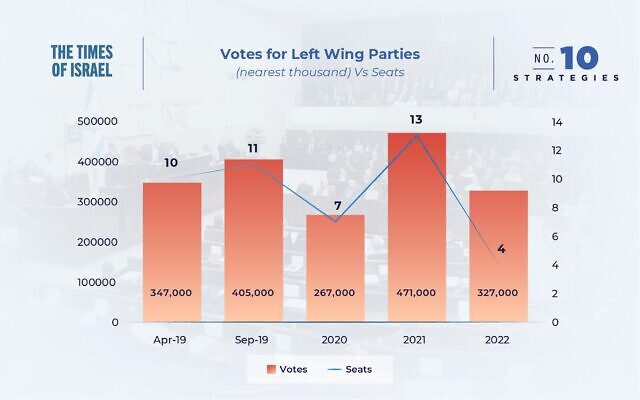

On the other side of the map, the situation was completely different. With four parties hovering just above the threshold and another just below, there was always a strong chance of missed votes that could prove costly. In the end, the veteran left-wing Meretz party fell by nearly 4,000 votes from the threshold, while Labor nearly passed it. The result meant that although the two left-wing parties won enough votes for about eight seats, they ended up with just four.

This sparked a wave of recriminations between the left and the center.

Without getting into the blame game, we’d like to highlight a point made repeatedly in these pages throughout the campaign: when elections develop a head-to-head dynamic, with two large parties vying to be the largest, voters tend to engage from smaller parties at the last minute. While Meretz has crossed the threshold in every poll over the past two months (albeit roughly), this dynamic means that its fall to the bottom shouldn’t come as a surprise.

Meretz party leader Zahava Galon casts her vote at a polling station in Bnei Brak, during the Knesset elections on November 1, 2022 (Roy Alima/Flash90)

As for the other party that did not cross the threshold, it was the Balad al-Arab Party, which ended up obtaining 2.9 percent, or nearly 15,000 votes. This means that while the Arab parties collectively won 511,000 votes, which roughly equals religious Zionism, they ended up with only ten seats. In the end, the 130,000 Arab vote increase since the last election, and successful efforts to increase their turnout, have been largely meaningless.

In all, the anti-Bibi bloc lost 289,000 votes, equal to about seven seats – the difference between a very close election and a resounding defeat.

What about the poll?

As always, when election results do not align with the ballot, questions are asked about the quality – and even usefulness – of public opinion polls. This has become a familiar argument around the world, and as those who have noted the accuracy of Israeli polling have noted in recent cycles, this is an important question we must address.

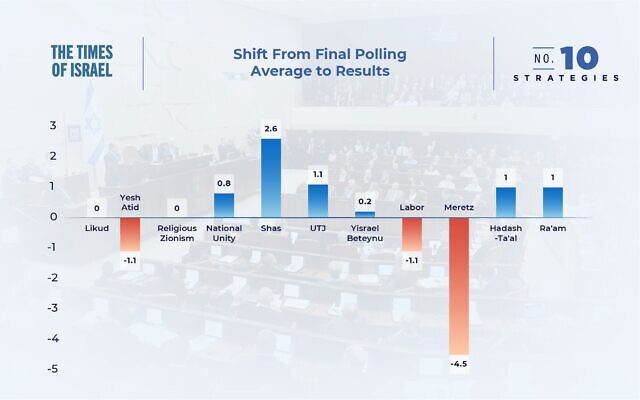

The biggest challenge for pollsters in Israel lies in the threshold. Meretz fell below the threshold by about 0.1 percent, far exceeding the accuracy of any poll. This in turn strengthened the other parties, as the Meretz vote was allocated elsewhere, further fueling the poll’s perception of being “wrong.”

If we’re too critical, we can point to the fact that Meretz averaged 4.6 seats in the final rating, not even dropping in a single poll, but nonetheless, polls showed it was always in the danger zone – always at home. Margin of error – and the fact that it shouldn’t come as a huge surprise.

Shas party leader Aryeh Deri with his supporters as the results of the Israeli elections were announced in Jerusalem. November 1, 2022 (Yossi Zamir/Flash90)

Had Meretz received an additional 4,000 votes, Netanyahu’s bloc would have won 61 seats, or more likely, 62, not far from the polling average of 60.3. Further analysis would be able to expand on this further, but it is possible that the late rise in turnout among the right, and especially among the Haredim, was responsible for this discrepancy.

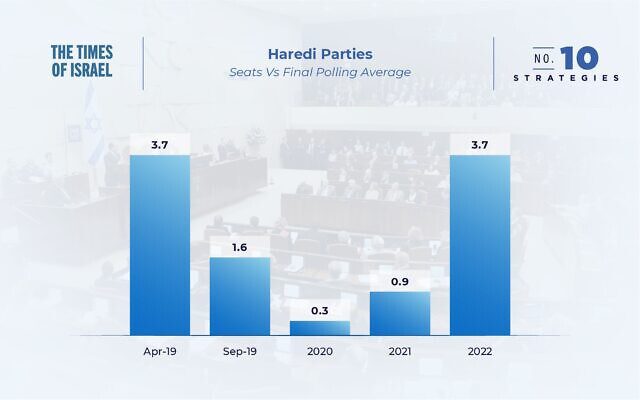

But on the subject of Haredi parties, there is much room for improvement. Despite continuous voting for 15 seats during the election campaign, the Haredi parties eventually won 19 seats, the fifth consecutive time they have exceeded their turnout. Twice – in April 2019 and this time – this was by a very large margin.

Given the special nature of the Haredi community, Israeli polling companies will need to invest more in new ways to reach this community more accurately going forward to ensure this does not happen again.

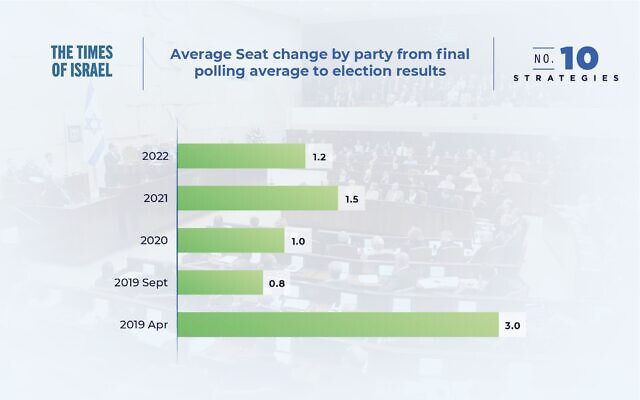

In general, the polling was very accurate. With the exception of Meretz and the Haredim, every other party ended up with a seat on average, with many of them in the lead. In a hyper-fluid multilateral field, this can’t be sniffed.

Moreover, even with Meretz losing the threshold, the average “error” by the party in this election was 1.2 seats, which is well in line with the average over the past four rounds.

In the end the survey achieved its goal of giving us an accurate picture of the state of the race. He showed us that the election would go straight to the corps, a seat or two on either side from 60 to 60, unless a party on the left drops below the threshold. It also showed us that four parties were very close to that threshold. While he wasn’t able to decide which party would eventually go down, he did his job.

Which brings us back to Where did we start? With this column, four long months ago, with our borrowed and misappropriated quote from Winston Churchill: After five election campaigns in quick succession, the truth is that polling is still the worst way to measure public sentiment, except for all the others that have been tried.

–

Simon Davies and Joshua Hantman are partners at Number 10 Strategies, an international strategy, research and communications consulting firm that has surveyed and campaigned for presidents, prime ministers, political parties and major corporations across dozens of countries on four continents.

“Internet practitioner. Social media maven. Certified zombieaholic. Lifelong communicator.”